This month marks the 100th birthday of the late Ewing Marion Kauffman, one of the most influential business leaders that Kansas City has ever produced.

That legacy started with pharmaceutical giant Marion Labs, but grew to encompass the Kansas City Royals, the Kauffman Foundation and a wide range of philanthropic projects. Ewing Kauffman is Exhibit A for the positive impact that an entrepreneur can exert on a community.

But there’s one facet of his story that doesn’t always receive as much attention: Many of Marion Labs’ associates would go on to create or staff other high-growth companies.

A few years ago, a researcher with the University of Bern in Switzerland, Heike Mayer, built a “genealogy” of Kansas City’s technology companies and the organizations that helped spawn them—organizations such as Cerner, Sprint, MRI Global and, yes, Marion Labs.

Compared to places like Boston and Silicon Valley, where most innovations can be traced back to their region’s research institutions, more Kansas City tech companies had their roots in the city’s large employers, Mayer found.

She discovered more than 20 companies, not counting the Kauffman Foundation and its programs, that had Marion ties. The only other company with as many offspring was Sprint.

Many of Marion’s descendants are pharmaceutical companies, naturally—that was Kauffman’s expertise. But his entrepreneurial heirs include technology companies, too, and marketing firms and consulting businesses and small manufacturers.

Case in point: TrippNT, a Northland business that makes carts for the world’s leading labs, was founded by Susan Tripp, a former Marion chemist. American Stair-Glide, an early Marion acquisition, produced electric chair lifts for the home. (It was later bought and eventually closed by ThyssenKrupp.)

Several of these companies have changed hands over the years—often for high-dollar sums. EPIQ Systems, a creator of legal software, is set to be acquired in a $1 billion deal announced this summer. Leawood-based Enturia and its ChloraPrep products sold for $490 million in 2008.

Many are still growing. Pharmaceutical marketing firm Intouch Solutions now employs a team of more than 650 people and regularly wins industry awards for its work. Teva Neuroscience, whose solutions help fight multiple sclerosis, continues to employ hundreds of people locally.

Marion Labs’ DNA

Marion Labs didn’t just inspire the creation of new companies. Marion also affected how its former employees would operate their own businesses. Several Marion alums said they patterned their workplace culture on Kauffman’s.

“Ewing Kauffman had ways to really influence performance through culture, and that’s sort of lost in so many ways today,” said Jim Laufenberg, the president and CEO of IGXBio, a local company that is developing immunotherapy solutions to fight HIV.

Laufenberg grew up at Marion Labs; he joined the company when he was just 23. So when he left in the mid-1990s, he experienced a little culture shock when he realized that most organizations don’t function as well as Marion did.

At Marion Labs, there was a sense of trust and belonging—everybody was in it together. “This culture was there,” Laufenberg said. “It influenced honesty and commitment and integrity.”

People trusted Kauffman because he practiced two basic leadership habits. One, treat others like you want to be treated—follow the Golden Rule, basically.

And two, those who produce the results should share in the rewards. Early on, Marion Labs instituted a profit-sharing plan that was very progressive for its time and industry. When the company sold, more than 300 employees became millionaires.

Sharing the rewards doesn’t always mean money—it can also translate to giving others credit. Laufenberg remembers the time that Kauffman came up to him at an event and presented him to some other guests. “He introduced me: ‘This is Jim, and he helped me build this company.’”

Kauffman would send handwritten thank-you notes, said Barb Geiger, a former Marion Labs associate who would later start her own contract research organization, Worldwide Clinical Research.

Today, Geiger is an executive vice president with Clinipace Worldwide, which her company merged with about seven years ago. Clinipace employs approximately 700 people around the globe.

Kauffman’s notes left a huge impression on Geiger: “This was the head of the company that took the time to do that.” She still makes a point of writing out her own thank-you notes.

Faruk Capan, the founder of Intouch Solutions, credits a lot of his company’s success to the leadership lessons he learned at Marion Labs. When he started Intouch from his home with a single employee, he knew he wanted to emulate Kauffman’s commitment to customer service.

“I fell in love with the culture of the company,” Capan said. “He was a really down-to-earth person as a leader.”

Because of his Marion ties, “I’ve been helped many times in the business,” Capan said, “really helping me open doors or make introductions.” Case in point: Capan received training through the Helzberg Entrepreneurial Mentoring Program, which was founded by Barnett Helzberg Jr.—who was himself mentored by Ewing Kauffman.

Why Small Businesses Need Companies Like Marion

The success of the Marion Labs alumni isn’t just a feel-good story. The company is also a useful lesson for communities that want to encourage more startups and high-growth businesses.

It’s one of the counterintuitive facts of entrepreneurial ecosystems: If you want to see more startup businesses in your community, it helps if you already have some big established firms (like Marion Labs) to be active players.

Peter Cohan, a lecturer on strategy at Babson College in Wellesley, Mass., refers to them as “pillar companies.” These are large, local companies, ones that are usually traded publicly. They invest in early-stage startups, become their customers and, in some cases, end up acquiring them.

Just as important, pillar companies create a surplus of talent in a community, Cohan said. They hire and train people who help the pillar company grow—and who eventually go off to start businesses of their own.

“I think a key reason why so many pillar companies are effective is the kind of people they hire,” Cohan said. “They basically learn how to create businesses.” (All big employers aren’t automatically pillars, he added—a large employer that insists on overly restrictive noncompete agreements could essentially bottle up a region’s supply of potential founders.)

But, if you put enough talented, entrepreneurially minded people together, amazing things can happen.

“The social network is a critical asset in business creation,” said Randy Schwering, an associate professor at Rockhurst University’s Helzberg School of Management.

Just look at Cerner, said Jeffrey Hornsby, director of the Regnier Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. The company’s founders started kicking around business ideas on walks during their work breaks from Arthur Andersen.

“When you hire people with an entrepreneurial mind-set, especially in this day and age, there’s a lot of synergy that happens,” Hornsby said.

Only a minority of entrepreneurs—maybe 25 percent—go directly from college to launching a startup, Hornsby noted. Most founders get 9-to-5 jobs with larger companies so they can pay off debt, save up money and learn how business works in the real world.

Of course, it’s possible for larger companies to hold onto many of these would-be founders by engaging them in “corporate entrepreneurship.” In those cases, the company has taken an idea or a piece of R&D and tried to build a business unit or even an entire company around it.

That’s how Laufenberg got one of his earliest tastes of startup life. He was part of a small team at Marion that launched an artificial-skin product. The team had to develop pitches and seek out resources from an investor—in this case, the parent company.

“The things that entrepreneurs do,” Laufenberg said, “we had to do within the company.”

When a region’s business environment is healthy, it looks a lot like a well-functioning ecosystem. Diversity and flexible connections keep the system resilient and adaptable to change and new opportunity. Big companies lead to the birth of new small businesses, a few of which will become major employers. Those lead to more new businesses, and the cycle continues.

“You’re not going to get the next large company unless you get the small company and the startup,” Hornsby said.

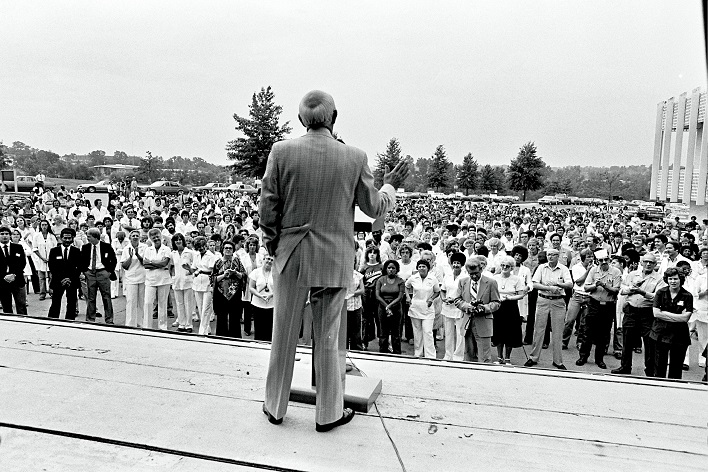

(photos courtesy of the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation)